Dark Matter Matters

culture

Five ways to strengthen your company’s immune system

I’m not usually a germophobe, but the last few months I’ve been walking around opening doors with my elbows and washing my hands constantly. I’ve been freaked out by the constant updates on Facebook about what my friends/friends’ kids have come down with now. So far, my immune system has held up pretty well, but I always worry that H1N1 is only a doorknob away.

These are trying times for corporate immune systems too. The economic meltdown has exposed corporations to all sorts of risks they don’t deal with in the regular course of business. Many corporate immune systems have failed, putting millions of people out of work. It begs the question: how resilient is your company? And how can you make your corporate immune system stronger?

These are trying times for corporate immune systems too. The economic meltdown has exposed corporations to all sorts of risks they don’t deal with in the regular course of business. Many corporate immune systems have failed, putting millions of people out of work. It begs the question: how resilient is your company? And how can you make your corporate immune system stronger?

I got to thinking about this corporate immune system concept after reading the new book The Age of the Unthinkable: Why the New World Disorder Constantly Surprises Us And What We Can Do About It by Joshua Cooper Ramo. In this fantastic book, Ramo (former foreign editor of Time Magazine, now a foreign policy/strategy consultant at Kissinger Associates) offers his thoughts on what we as a society need to do to adapt to a rapidly changing world.

Ramo talks a lot about the idea of creating a stronger global immune system. Here’s what he means:

“What we need now, both for our world and in each of our lives, is a way of living that resembles nothing so much as a global immune system: always ready, capable of dealing with the unexpected, as dynamic as the world itself. An immune system can’t prevent the existence of a disease, but without one even the slightest of germs have deadly implications.”

Ramo presents this in idea in the context of how we protect ourselves from a scary world– terrorists, rogue nations, nuclear proliferation, and all that, but the concept applies well to the corporate world as well– tough competitors, fickle customers, shrinking budgets– we corporate folks have our own demons.

So how do we shore up the ol’ immune system? Ramo refers to the philosophy of building resilience or “deep security” into the organization. Continue reading

Help! Who the heck are you? (a poll)

When I first started this blog, my hope was to create a home for an open source perspective on brand, culture, and community issues in communications and business.

I figured there might be some people out there in business-land who don’t really understand all this open source stuff too well, and would like to hear more about how the open source way might apply to the issues they face in their work. After all, lots of folks are writing about open source in the macro business context (Chris Anderson, Malcolm Gladwell, Gary Hamel, Tom Peters among many others), but not too many of them work inside an open source business.

I have a sense from the comments I get that there are quite a few readers who have already drank the open source kool-aid too (thank you, friends!). I may not always have as much to offer you, but I love getting your comments and ideas because they make me work harder, give me new ideas, and they often force me to challenge my thinking about open source.

I definitely want to understand who is coming here a bit better. So today, a simple question– who are you?

Thanks for responding, hopefully it’ll help me make this a more interesting place!

Howard Schultz of Starbucks: The role of culture in a crisis

This week I was lucky enough to attend the Ernst & Young Strategic Growth Forum in Palm Desert, CA. As you may recall, last year Red Hat Chairman Matthew Szulik was the national Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year, and later this week, he’ll hand over his title to the next entrepreneur in waiting. One of the most exciting things about the Strategic Growth Forum is that it brings together some of the smartest entrepreneurial minds in the world in one place, and this morning, I had an opportunity to hear from one of the best.

Howard Schultz, Chairman, President, and CEO of Starbucks, who won an Entrepreneur of the Year award in 1993, spoke about his experience leading Starbucks through the economic crisis. As Starbucks began going through hard times, Schultz, who had given up the CEO role in 2001 (while remaining Chariman), decided it was time to take back the CEO responsibilities himself in early 2008.

Why? He was worried that the distinct culture, mission, and values that had brought the company great success were eroding.

According to Schultz, he came back into an operational role because he felt that the way out of crisis was not a simple change in business strategy, but instead– in his words– “love and nurturing.” His key to turning things around was revitalizing the investment in his people, recommitting to the core purpose of the organization and providing employees with hope and inspiration.

He says the transformation of Starbucks since this revitalization has been key to a tremendous amount of new innovation happening inside the company. People have even commented to him that it reminds them of what the early days at Starbucks must have been like.

Schultz took 10,000 of his best people and brought them together in New Orleans in late 2008 for a leadership conference where they spent 50,000 volunteer hours helping communities re-build after Hurricane Katrina. Below is a documentary that was filmed about this event.

Maslow’s hierarchy of (community) needs

Over the past month or so, I’ve been having a conversation with Iain Gray, Red Hat Vice President of Customer Engagement, about the ways companies engage with communities. I’ve also written a lot lately about common mistakes folks make in developing corporate community strategies (see my two posts about Tom Sawyer community-building here and here and Chris Brogan’s writeup here).

One idea we bounced around for a while was a mashup of community thinking and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. For those of you who slept in with a bad hangover the day you were supposed to learn about Maslow in your intro psych class (damn you, Jagermeister!), here is the Wikipedia summary:

“[Maslow’s hierarchy of needs] is often depicted as a pyramid consisting of five levels: the lowest level is associated with physiological needs, while the uppermost level is associated with self-actualization needs, particularly those related to identity and purpose. The higher needs in this hierarchy only come into focus when the lower needs in the pyramid are met. Once an individual has moved upwards to the next level, needs in the lower level will no longer be prioritized. If a lower set of needs is no longer being met, the individual will temporarily re-prioritize those needs by focusing attention on the unfulfilled needs, but will not permanently regress to the lower level.”

Now granted, the needs of a company are very different than the needs of a human being. At its very basic level, a company has a “physiological” need to make money. If that need is not being met, little else will matter. But in an ironic twist, this basic need to make money can actually hinder the company’s ability to make money if it is not wrapped in a more self-actualized strategy.

To explain what I mean, think about the last annoying salesperson who called or emailed you. Why were you annoyed? Probably because it was very clear to you that the salesperson was badly hiding his basic motivation to make money. He wasn’t talking to you because he valued you– he was talking to your wallet.

Now think about the best recent sales experience you’ve had. Mostly likely, this salesperson was being motivated by a higher purpose, perhaps something as simple as a desire to make you happy. Sometimes the most effective salespeople aren’t even in sales at all– like a friend who tells you about a new album you should buy, for example. Or sites like Trip Advisor, where you can learn about where to go on vacation from other folks like you.

When it comes to community strategy, most companies have trouble finding motivation beyond the simple need to make money– and the communities they interact with can tell.

Yet if you look at the greatest companies out there, you’ll find that they usually have a strong sense of identity and purpose– just like Maslow’s self-actualized people. Read anything by Jim Collins and you’ll see what I mean.

For a recent presentation, Iain developed a chart that looks a lot like the one below. And to embarrass Iain, let’s call it the Gray hierarchy of community needs.

The latest in the search for dark matter

As people who’ve been reading this blog for a while know, it’s called Dark Matter Matters because I see some similarities between the struggle that physicists and astrophysicists are going through attempting to find and measure dark matter and dark energy in the universe and the struggle among marketing and communications professionals trying to quantify and measure the value of their investments in brand, culture, and community. Read more in my intro article here.

From time to time I like to keep all the marketing folks up to date on how their colleagues in physics are doing on the whole dark matter thing, and there’s been some interesting news over the past week.

First, there was an article in the New York Times on Saturday saying that scientists have discovered a mysterious haze of high-energy particles at the center of the Milky Way. Some think these particles may be the decayed remains of dark matter. From the article:

At issue is the origin of a haze of gamma rays surrounding the center of our galaxy, which does not appear connected to any normal astrophysical cause but matches up with a puzzling cloud of radio waves, a “microwave haze,” discovered previously by NASA’s WMAP satellite around the center. Both the gamma rays and the microwaves, Dr. Dobler and his colleagues argue, could be caused by the same thing: a cloud of energetic electrons.

The electrons could, in turn, be the result of decaying dark matter, but that, they said, is an argument they will make in a future paper.

Clearly the authors of the research are still hedging their bets, and other scientists apparently believe the findings are inconclusive. There will need to be still more research before anything gets proven for sure.

Meanwhile, our good friends in charge of the Large Hadron Collider, which has been out of commission for the last year, are about ready to roll again after the massive failure last September that caused catastrophic damage. The Large Hadron Collider is an enormous, multi-billion dollar supercollider built underground beneath France and Switzerland by physicists trying to prove, among other things, the existence of dark matter (funny side note, read this article about how the collider might be being sabotaged from The Future). Good article in The Guardian yesterday here on the current status. From the article:

Cern scientists have begun firing protons round one small section of the collider as they prepare for its re-opening. Over the next few weeks, more and more bunches of protons will be put into the machine until, by Christmas, beams will be in full flight and can be collided.

The LHC will then start producing results – 13 years after work on its construction began.

So stay tuned. The physicists are getting closer– if only we marketing folks were doing as well!

Love, hate, and memo-list

Top management experts are now acknowledging the importance of creating forums and contexts inside corporations that allow peer review, transparency, and powerful natural hierarchies to flourish. Here’s one great post by Gary Hamel from earlier this year that Iain Gray pointed out today. We’ve had an open forum exactly like this at Red Hat for a very long time. We call it memo-list.

When any new employee comes into Red Hat, memo-list is one of the first great shocks to the system. Memo-list itself is not some technological marvel of a collaboration tool– it is just a simple, old skool mailing list where any Red Hat employee can post an email message that goes out to virtually every employee in the company. That’s 3000+ folks.

Memo-list has been a hot issue inside the walls of Red Hat since before I joined ten years ago. Folks tend to either love it or hate it.

Some people are shocked by the fact that any employee can publicly challenge a post by an executive or even the CEO in an email to memo-list (and they do). Some people are annoyed by the discussions that appear over and over, year after year. Some people view it as idle chitchat and a waste of time.

But some people view it as the backbone of the Red Hat culture. A place where the power of meritocracy is nurtured. Where the employees force transparency, openness, and accountability. Where peer review makes for better ideas (after all, given enough eyes, all bugs are shallow).

I love memo-list, warts and all (I think Gary Hamel would like it too). In my view, it is the single most important thing that differentiates the Red Hat culture from most other corporate cultures.

John Seely Brown’s secret formula for an innovation culture

I spent today at the Coach K Leadership Conference at Duke University (Red Hat CEO Jim Whitehurst will be speaking there tomorrow morning). One of today’s highlights was a panel called “Leading the Creative Enterprise” featuring John Seely Brown (the former director of the famous innovation hub at Xerox PARC).

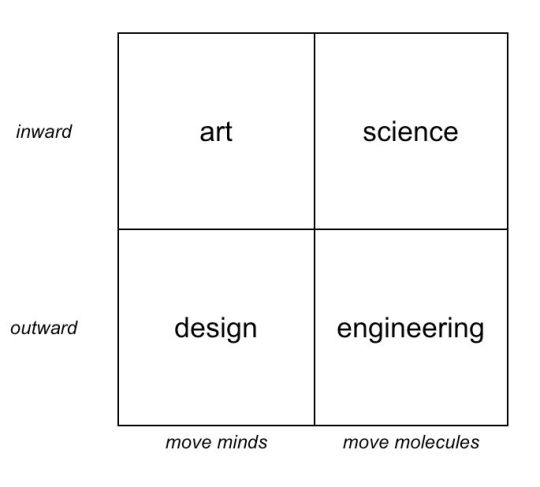

I always love it when really smart people boil down the world into a simple 2×2 matrix, and during his comments, JSB put a chart up on the screen that looked something like this:

To create a culture that will be successful at innovating, JSB says you must have four types of people: artists, scientists, designers, and engineers working together; each group must be represented.

To create a culture that will be successful at innovating, JSB says you must have four types of people: artists, scientists, designers, and engineers working together; each group must be represented.

Two of the groups (the artists and the scientists) get their energy from the way they internally process their own ideas, while the other two groups (designers and engineers) get their energy by thinking about how those ideas are brought to the outside world.

Looking at the matrix the other way, artists and designers share a common cause of trying to move people’s minds while scientists and engineers are firmly grounded in the world of actually making stuff work beyond the idea itself.

I’ve certainly seen these roles all represented in projects at Red Hat that have resulted in great innovations (the group that worked on the Red Hat values years ago comes to mind). And I’ve also been a part of projects that failed because at least one perspective was missing.

What do you think? Does this matrix work for you?

Gary Hamel: Open Source is one of the greatest management innovations of the 21st century

My colleague John Adams, reporting from the World Business Forum in New York, wrote on Twitter yesterday that during his speech, management guru Gary Hamel called open source one of the greatest management innovations of the 21st century (coverage of Gary’s speech here and here).

I love it. Gary Hamel is a hero of mine, and many consider him one of the greatest business minds on the planet. I’ve written about him, well, too much (start here, here, and here), and I follow him via his website, his non-profit called MLab, and his Wall Street Journal blog.

I knew Gary was familiar with open source after reading his book The Future of Management (one of the top ten books behind Dark Matter Matters). He spends five pages (205-210 in the hardcover) discussing open source and at one point says the following:

The success of the open source software movement is the single most dramatic example of how an opt-in engagement model can mobilize human effort on a grand scale… It’s little wonder that the success of open source has left a lot of senior executives slack-jawed. After all, it’s tough for managers to understand a production process that doesn’t rely on managers.

Here’s his analysis of why the model works so well:

Brands are like sponges, people

On Twitter yesterday, my friend Chris Blizzard mentioned to someone that I often say “brands are like sponges.” When I saw this, I realized that a) I haven’t said this in a while and b) I should say it more often because it is a freakin’ awesome way to think about brands. So I’m saying it again right now. Right here.

It’s actually not my line. I got it from the Scott Bedbury book A New Brand World (one of the top ten books behind Dark Matter Matters). Near the beginning of the book, Scott, who is one of the masterminds behind the good ol’ days of the Nike brand in the 80s and the Starbucks brand in the 90s, provides one of my favorite definitions of what a brand is:

A brand is the sum of the good, the bad, the ugly, and the off strategy. It is defined by your best product as well as your worst product. It is defined by award-winning advertising as well as by the god-awful ads that somehow slipped through the cracks, got approved, and, not surprisingly, sank into oblivion. It is defined by the accomplishments of your best employee– the shining star in the company who can do no wrong– as well as by the mishaps of the worst hire that you ever made. It is also defined by your receptionist and the music your customers are subjected to when they are placed on hold. For every grand and finely worded public statement by the CEO, the brand is also defined by derisory consumer comments overheard in the hallway or in a chat room on the Internet. Brands are sponges for content, for images, for fleeting feelings. They become psychological concepts held in the minds of the public, where they may stay forever. As such, you can’t entirely control a brand. At best you can only guide and influence it.

Those last two lines have stuck in my mind since I first read them. First, the idea that a brand is a sponge, soaking up everything, both good and bad. And second, that you cannot control a brand, you can only guide and influence it.

Jim Whitehurst: 20th century companies already hiring 21st century employees

Last night, Red Hat President and CEO Jim Whitehurst gave a talk to a group made up of mostly students and faculty at the NC State School of Engineering. Nice writeup of it in the student newspaper here. His ideas were very timely for me; just the other day, I wrote a post with some tips for companies with 20th century cultures trying to make the move into the 21st century.

Your future employee sez: I'm going to need a bit more collaboration and meritocracy up in here! (photo by D Sharon Pruitt)

Jim Whitehurst is in a rather unique position because he has managed both an icon of the 20th century corporation (Delta Airlines) and what we’d like to think is a good example of the 21st century corporation here at Red Hat.

Because of his experiences, Jim is able to clearly see and articulate the differences between the old model of corporate culture, based on classic Sloan-esque management principles, and the emerging model, based in many ways on the power of participation broadly (and in our case, the open source way specifically).

One very simple point Jim made that really struck me: Companies with 20th century business models need to realize that they are already hiring 21st century employees.

People coming out of school today have grown up in an age where the ability to participate and share broadly is all they’ve known. These folks have grown up with email accounts, the Internet, Facebook, and all of the other trappings of a connected world.

So when they graduate from school and take jobs working in old-style corporate cultures, where progressive principles like transparency, collaboration, and meritocracy lose out to the old world of control, power, and hierarchy, what happens?