Dark Matter Matters

brand

Brand naming strategy: branded house or house of brands?

At Red Hat, I often get questions about how we name stuff. It is usually not just idle curiosity, mind you, in most cases someone has a new program or product and would like to call it something like Supersexyshinyfoo. Our team has to play the bad guy role and explain that we don’t usually create new brands like that at Red Hat.

The response is typically something like “Let me get this straight… You guys think long, boring names like Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Red Hat Enterprise Virtualization, and JBoss Enterprise Application Platform are better than Supersexyshinyfoo?”

My answer? We already have a Supersexyshiny… it’s the Red Hat brand.

We’ve spent years building the Red Hat brand into something that people associate with (according to our surveys) value, trust, openness, choice, collaboration, and a bunch of other neat things. Studies have shown that Red Hat brand karma is pretty positive. And the logo looks great on a t-shirt. Our brand is one of our most valuable assets.

This is why most Red Hat products have very descriptive (some would say boring…) names. The equation probably looks something like this:

(Supersexyshiny + Foo) = (Red Hat + descriptive name)

This brand strategy is often referred to as a “branded house” strategy. Take one strong brand, plow all of your brand meaning into it, while differentiating each product with descriptors instead of brand names.

These days, many automobile manufacturers do things this way. Remember when Acura used to have the Acura Integra and the Acura Legend? Honda simplified the branding strategy by moving to RL, TL, TSX, etc. as descriptors for their cars, pointing all of the brand energy back at the Acura brand. Many other auto manufacturers follow similar principles.

Tom Sawyer, whitewashing fences, and building communities online

I spoke on a panel at GE today with Chris Brogan, author of the book Trust Agents (almost finished with it, more comments in a later post…).

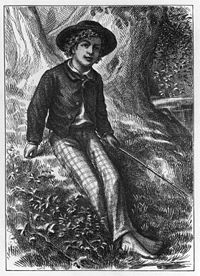

After hearing Chris talk about building trust in online communities, it hit me that one of the biggest mistakes I’ve seen people make when trying to build communities online, even in the open source world, is that they think like Tom Sawyer.

Here’s how Wikipedia retells the story of Tom Sawyer and the fence:

After playing hooky from school on Friday and dirtying his clothes in a fight, Tom is made to whitewash the fence as punishment on Saturday. At first, Tom is disappointed by having to forfeit his day off. However, he soon cleverly persuades his friends to trade him small treasures for the privilege of doing his work.

When thinking about building communities online, are you thinking like Tom Sawyer? Why are you building a community in the first place? When it comes right down to it, do you really just want people to whitewash your fence for you and give you small treasures in return for the privilege?

If you are looking to ideas like open source or social media as simple means to get what you want for your company, it’s time to rethink your community strategy.

Wait, what if dark energy doesn’t matter?

The horror! A few days ago, in a study released in one of my favorite light reading mags, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, two mathematicians proposed that dark energy might simply be an illusion we observe from our spot in a massive space-time expansion wave. There’s a nice writeup of the research in National Geographic here.

Does this mean the entire concept of this website, that brand, culture, and community form the dark matter and dark energy of organizations, breaks down too? That all this hippie brand-building, culture-growing, community-creating stuff is also an illusion, and the traditional visible mechanics of business alone are the stuff of which great companies are made?

Does this mean the entire concept of this website, that brand, culture, and community form the dark matter and dark energy of organizations, breaks down too? That all this hippie brand-building, culture-growing, community-creating stuff is also an illusion, and the traditional visible mechanics of business alone are the stuff of which great companies are made?

I know. I know. It rocked my foundation too. Well, as my favorite fortune cookie fortune once told me, “all is not yet lost.” It is just a theory.

And it turns out that for the theory to be true, for the math to work, we must be at the center of the universe, a caveat that one physicist describes as “unusual.” I’d say so. Didn’t Copernicus have something to say about that in, like, 1543?

If you are still concerned and want to learn more, go read the abstract of the report. I’ll give you a taste to whet your appetite:

We derive a system of three coupled equations that implicitly defines a continuous one-parameter family of expanding wave solutions of the Einstein equations, such that the Friedmann universe associated with the pure radiation phase of the Standard Model of Cosmology is embedded as a single point in this family. By approximating solutions near the center to leading order in the Hubble length, the family reduces to an explicit one-parameter family of expanding spacetimes, given in closed form, that represents a perturbation of the Standard Model.

These guys seem pretty smart, and it sounds like we stand to learn a lot from their findings. And what’s good enough for the National Academy of Sciences is good enough for me.

As for our little Dark Matter Matters website, I’m no mathematician, but I see a lot of prominent mathematicians and physicists calling these results controversial. For now, I’m still thinking dark matter and dark energy might matter, people. Carry on.

Sharing your brand story (and here’s ours)

The most compelling brands in the world tell compelling stories. Whether the brand is Nike (the Greek winged goddess of victory was named Nike, and it all rolls from there) or IBM (Thomas Watson and THINK) or [your favorite brand here], the most interesting brands have great mythologies built up over time. The brand story is deeply ingrained in their actions, voice, look, and culture.

It’s been almost eight years since we created the first Red Hat Brand Book. The original book was an attempt to capture the essence of our Red Hat story, to explain what Red Hat believes, where we came from, and why we do what we do.

It had a secondary mission as an early brand usage guide, explaining what Red Hat should look and sound like at a time when the company was expanding rapidly around the world and brand consistency was becoming harder to achieve.

When most companies create this sort of document, they call it a “Brand Standards Manual”, or something like that. But we were young, foolish, and drunk on the meritocracy of open source, so in the first version of the Brand Book, we emblazoned the words “This is not a manual” on the front cover.

Why? We wanted to be very clear this book was the starting point for an ongoing conversation about what the Red Hat brand stood for, looked like, and sounded like, rather than a prescriptive “Thou shalt not…” kind of standards guide.

I hate brand standards that sound like legal documents. I’ve always felt like the role of our group was to educate and inspire, not to police, and we tried to create a document that embodied that spirit.

This year we launched the biggest update yet to the Brand Book. In doing so, we actually split it into two projects:

Matthew Szulik and the Red Hat vision

The BBC conducted a great interview with Red Hat Chairman Matthew Szulik while he was attending the Ernst & Young World Entrepreneur of the Year awards recently (representing the United States as our winner). You can listen to it here.

(representing the United States as our winner). You can listen to it here.

This interview is a wonderful reminder of the powerful impact of a corporate vision that extends beyond just making money. And a great reminder for me of how lucky I have been to learn about leadership, community, culture, and brand from the 2008 United States Entrepreneur of the Year.

If you are interested in learning more about Matthew Szulik, his vision, and how it evolved, here is a wonderful oral history of his life that was commissioned a few years ago.

Brand positioning tip #4: brand permission

In brand positioning tips 1-3, we discussed the 4 elements of good brand positioning: points of difference, points of parity, the competitive frame of reference, and the brand mantra. In this post, we are going to switch gears and talk about a subject called brand permission.

When attempting to position your brand in a new competitive frame of reference (or, in non-marketing-ese, when you want to start selling stuff in a new market), consider whether your brand has earned permission to enter that market.

When attempting to position your brand in a new competitive frame of reference (or, in non-marketing-ese, when you want to start selling stuff in a new market), consider whether your brand has earned permission to enter that market.

How do you know if you have permission? And who do you need permission from? Well, let’s look at a few examples.

Back in the early 1990s, Clorox underwent a failed experiment in extending the Clorox brand into detergent. There is a nice short writeup of it here. Why did the detergent product fail?

Brand positioning tip #3: the brand mantra

In previous posts, we’ve covered three of the four elements of good brand positioning as I learned them from Dr. Kevin Keller,  author of the classic branding textbook Strategic Brand Management:

author of the classic branding textbook Strategic Brand Management:

- Points of difference: the things that make you different from your competition (and that your customers value)

- Points of parity: the places where you may be weaker than the competition and need to ensure you are “good enough” so you can still win on the merits of your points of difference

- Competitive frame of reference: the market or competitive landscape in which you are positioning yourself

Today we will be covering the 4th element of good brand positioning: the brand mantra.

What is a brand mantra?

A brand mantra is a 3-5 word shorthand encapsulation of your brand position. It is not an advertising slogan, and, in most cases, it won’t be something you use publicly.

According to Scott Bedbury, author of A New Brand World (one the of top 10 books behind Dark Matter Matters), the term brand mantra was coined during his time at Nike.

Brand positioning tip #2: the competitive frame of reference

In Brand Positioning Tip #1, we covered 2 of the 4 key elements of successful brand positioning done the way Dr. Kevin Keller taught me: points of parity and points of difference. Today, I’d like to highlight the third key element of good brand positioning– understanding your competitive frame of reference.

Competitive frame of reference is a fancy way of saying “the market you compete in.”

This sounds pretty simple, huh? It can be… If you run a furniture store, your competitive frame of reference would probably be the furniture market. If you run a tattoo parlor, your competitive frame of reference would probably be the tattoo market.

Those are pretty cut and dry cases. But have you ever stopped and wondered to yourself, “exactly what market am I competing in?” and realized that you are really competing in a market that is not initially obvious? Or that you are actually competing in multiple markets? If either of these situations are true, you may discover you need to create points of parity and points of difference for each market where you compete.

Here is an common example of a less-than-obvious competitive frame of reference.

What market do you think Starbucks is in? The coffee market? Maybe. In the coffee market, Starbucks competes with grocery stores, fast food restaurants, other coffee shops, and home brewers. Tough market… they aren’t competitive in the coffee market on price, there are probably options that (arguably) taste better, maybe have shorter lines. It’s hard to believe that Starbucks would have grown as big as they are by simply competing in the existing coffee market.

Measuring dark matter? We’re working on it.

Those of you who have been following this blog for a while know it is based on the simple premise that there are some things out there in the world that are pretty difficult to see or measure, yet these same things can often be the stuff with the biggest impact. The intro to the blog tells the full story.

In the world of astronomy, two of these things are dark matter and dark energy. Both hard to see and measure.

In the world of astronomy, two of these things are dark matter and dark energy. Both hard to see and measure.

In the world of business, three of these things are brand, culture, and community. Also tough to see and measure their impact in the business world.

So while we constantly explore ways to better understand the impact of brand, culture, and community here at Dark Matter Matters, the world of astronomy is trying to better understand exactly what the heck dark matter and dark energy are.

Thought it might be worth taking a short break from our regularly scheduled program to give an update on how the astronomers are doing.

Summer reading list for Dark Matter Matters

Ah, vacation… the time when the work shuts down for a few days and the Dark Matter Matters blog comes out of hibernation… 3 posts in 3 days!

A few months ago I wrote a post where I highlighted the top ten books behind Dark Matter Matters. In that post I promised to create a list of the books that didn’t make the top 10 cut, but are still pretty awesome.

So here, to celebrate the long holiday weekend, are some more books that have inspired Dark Matter Matters.

Books about how large-scale collaboration is pretty much the deal:

Wikinomics by Don Tapscott and Anthony Williams

The Wisdom of Crowds by James Surowiecki

The Starfish and the Spider by Ori Braffman and Rod Beckstrom

In the open source world, there’s a legendary quote attributed to Linus Torvalds (yes, he is the guy that Linux is named after) “Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.” The first two of these books are the extended dance remix of this quote. Each has a unique take, but both show how mass collaboration is changing everything about our society and the way we solve problems. The Starfish and the Spider is a interesting look at leaderless organizations and is a nice book for anyone trying to understand how the open source movement (and other leaderless organizations) work, and why open source is so hard to compete against. It is also a nice complement to the Mintzberg article I wrote about in my previous post.