Dark Matter Matters

community

Three approaches to designing brand positioning for ad-free brands

In my last few posts (here and here), I shared some tips for collecting and synthesizing the brand research you will use to design positioning for your brand. In this post, I’ll share three approaches to designing brand positioning I believe will work for the majority of brands:

• The lone designer approach

• The internal community approach

• The open community approach

Each of these approaches has strengths and weaknesses, and they can also be mashed up into a hybrid that better suits the culture of your organization.

The Lone Designer Approach

Are you a small organization or an organization of one? Perhaps you are attempting to position a website or simply get a small company off the ground on a foundation of solid positioning. If you found during the research phase that you were doing most of the work yourself and don’t want or can’t afford to bring others into the positioning process, you may be a good candidate for the lone designer approach.

The lone designer approach is exactly what it sounds like: a positioning process run by one person alone or by a very small group. The advantage of this approach is that you have complete control over the process. You won’t have to spend much time arguing with others over the exact words in your brand mantra; you won’t need to conduct time-consuming collaboration sessions; and you will only go down rat holes of your own choosing. The lone designer approach can be very efficient and is the least resource-intensive of the three approaches.

The downside of the lone designer approach is that it gives you no head start on rolling out your positioning to your brand community. By making your positioning process a black box and revealing only the finished product, you are taking some risks. First, the positioning you design might not resonate or, worse, might be ignored because you didn’t include input from others beyond the initial research. Second, you may have trouble getting others to help you roll it out or take ownership over its success because they had no role in creating it.

Usually I recommend the lone designer approach only to small or new organizations with no access to a preexisting community of employee or community contributors who care about the brand. If you already have a community of supporters around your brand—even if it is small—strongly consider one of the other two approaches (internal community or open community).

The Internal Community Approach

You understand the powerful impact that engaging members of your brand community in the positioning process might have on your brand. You believe your organization is progressive enough to allow employees to help with the brand positioning process. But you just don’t think your organization is ready to open up the brand positioning process to the outside world. If this sounds like your situation, the internal community approach might be the best option for your brand.

The internal community approach opens up the positioning process to some level of participation from people inside the organization. It may broadly solicit contributions from every employee, or it can simply open up the process to a hand-selected group of people representing the employee base.

The internal community approach to brand positioning is a smart, safe approach for many organizations. It makes brand positioning a cultural activity within the organization, allowing you to collect a broad range of interesting ideas and begin to sow the seeds for future participation in the brand rollout down the road. In addition, it can become a compelling leadership opportunity, helping develop future leaders of your brand as well.

While this internal approach is still community-based, it is usually perceived as less risky than an approach involving external contributors. You might find it easier to sell the internal approach to executives who fear opening up the organization to the outside world or think doing so will give the external community the perception the organization is confused or doesn’t know what it is doing because it is asking for help.

The Open Community Approach

Even though I’ll be the first to admit that it is not right for every brand, the open community approach is by far my favorite approach (as you can probably tell by now) and is a very effective one for ad-free brands. The open community approach opens the positioning process to contributions from members of both the internal and external brand communities. Running an open community brand positioning project is similar to running an internal community one. Both approaches have the advantage of bringing in a variety of viewpoints.

Both can create valuable brand advocates who will be helpful down the road. The open community approach just takes things as step further and allows people outside the organization to contribute as well. The benefit of this approach is that it can usually form the beginning of a constructive dialogue with all the people who care about your brand—not just those who work for your organization. It can help you build relationships based on trust, sharing, and respect with people in the outside world. And it can save you money and time by revealing flaws in your positioning much earlier in the process.

The downsides of an open approach? If the project is poorly organized or badly communicated, it really will realize the fears of some executives and show the outside world you don’t know what you’re doing. An open positioning approach requires a deft, highly skilled, effective communicator and facilitator. It requires coordination between different parts of the organization that are in touch with the outside world to ensure communication is clear and consistent.

But although the risks of opening up your positioning process to the outside world are higher, the rewards can be much bigger as well. By transparently opening a relationship between your brand and the outside world, you are embracing the future of brand management, accepting the role of your brand community in the definition of your brand, and proactively getting your community involved in a positive way.

You are beginning a conversation.

—

This is the sixth in a series of posts drawn from The Ad-Free Brand, which is available now.

Our story about the Wikimedia strategic planning project is on Harvard Business Review’s blog today

Polly LaBarre wrote a nice piece that was published on the Harvard Business Review blog today in which she highlighted the story that Philippe Beaudette, Eugene Eric Kim, and I wrote for the Management Innovation Exchange about the Wikimedia Foundation strategic planning project.

Polly LaBarre wrote a nice piece that was published on the Harvard Business Review blog today in which she highlighted the story that Philippe Beaudette, Eugene Eric Kim, and I wrote for the Management Innovation Exchange about the Wikimedia Foundation strategic planning project.

Basically, Eugene and Philippe organized and ran a strategic planning project that democratized what is usually a fairly aristocratic process, involving a community of 1000+ Wikimedia volunteers in helping craft strategy for the next five years.

Their story blew my mind when I first heard about it, and I hope it blows your mind too (but in a good way).

You can read Polly’s post here, then go check out the full story on the MIX.

An interview about communities of passion, the MIX, and HCI

The other day, Peter Clayton of Total Picture Radio interviewed me in preparation for the panel I’ll me moderating at the HCI Engagement and Retention Conference in Chicago in July.

We talked about the Management Innovation Exchange and I shared some ideas from the winning hacks and stories of the folks that will be on the panel: Lisa Haneberg, Joris Luijke, and Doug Solomon. In addition, we talked more broadly about communities of passion, employee engagement, and social media, among other things.

You can listen to the podcast here.

Are the “Best Companies to Work For” really the best companies to work for?

The other day I noticed that the application deadline to be considered for the Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work For list is this week. My company is too small to be considered for this honor (you must have at least 1000 employees), but I always pay close attention when the rankings come out, and I’m sure many of you do as well. On the 2011 list, the #1 company was SAS, followed by Boston Consulting Group and Wegmans (see all 100 here).

The other day I noticed that the application deadline to be considered for the Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work For list is this week. My company is too small to be considered for this honor (you must have at least 1000 employees), but I always pay close attention when the rankings come out, and I’m sure many of you do as well. On the 2011 list, the #1 company was SAS, followed by Boston Consulting Group and Wegmans (see all 100 here).

The organization that does the ranking, The Great Place to Work Institute, has been running this competition for years and has a rigorous process for selecting the final list.

Yet when I read the articles written about the top companies or browse the list in Fortune, I always feel like something is missing. I finally put my finger on it:

I believe the evaluation process is benefit-heavy and mission-light.

What do I mean? When I read about the top companies, most of the emphasis seems to be on the salary and benefits offered to employees; which companies pay the most and have the best or most unusual employee perks (life coaches, wine bars, or Botox anyone?).

But the section of the report I want to see is nowhere to be found:

Which companies are doing things that matter?

- Which companies have a noble mission or purpose and are helping make the world a better place?

- Which companies have a bold vision and are leading innovation that is changing the world?

- Which companies are doing such amazing or interesting stuff that they are attracting the world’s top talent?

You see, I’m not someone who would find a company a great place to work because it offers a big paycheck and fantastic benefits. I need my work to be personally fulfilling. I need to feel like I have a chance to make a difference, to do something great.

I don’t think I’m alone.

Previously, I’ve written about something I call cultural fool’s gold, my term for an organizational culture built exclusively on entitlements.

If you want to test whether you work in an entitlement-driven culture, just ask a few people what they like most about working at your company. If they immediately jump to things like free snacks and drinks, the work-from-home policy, or the employee game room, you may have a culture made of fool’s gold, an entitlement-driven culture.

If instead they say things like these:

- I believe in what we are doing.

- I love coming to work every day.

- I leave work each day with a sense of accomplishment.

- I am changing the world.

you probably work in the only type of organization I’d personally ever consider—a mission-driven organization.

So the big question I’d pose to the folks at the Great Place to Work Institute:

Should there be a “best places” list for those of us who not only want to work someplace great, but want to do something great?

Maybe the Institute should consider a new list for those of us who demand more from our workplaces than big salaries, comfortable benefits, and free Botox injections?

Perhaps it could be called Best Places To Do Great Work or Workplaces with Purpose for People With Purpose or something like that?

The world has changed. I think many of the people graduating for our universities today will demand more than just great benefits from their employers. They’ll want to do meaningful work and be a part of a community of others looking for the same.

Personally, I hope to see the way we rate “the best places to work” in the future change to accommodate people like me.

What do you think?

[This post originally appeared on opensource.com]

Three tired marketing words you should stop using

Over the years, I’ve had many people label me as a marketing guy just because I help build brands. I don’t like being labelled, but I particularly don’t like that marketing label. Why?

Over the years, I’ve had many people label me as a marketing guy just because I help build brands. I don’t like being labelled, but I particularly don’t like that marketing label. Why?

In my view, traditional marketing sets up an adversarial relationship, a battle of wills pitting seller vs. buyer.

The seller begins the relationship with a goal to convince the buyer to buy something. The buyer begins the relationship wary of believing what the seller is saying (often with good reason). It is an unhealthy connection that is doomed to fail most of the time.

What’s the alternative? I believe companies should stop trying to build relationships with those interested in their brands using a marketing-based approach and instead move to a community-based approach where the culmination of the relationship is not always a transaction, but instead a meaningful partnership or friendship that may create multiple valuable outcomes for both sides.

How do you do this? Consider beginning by eradicating three of the most common words in the marketing vocabulary: audience, message, and market.

So you better understand what I mean, let me attempt to use all three of these words in a typical sentence you might hear coming out of a marketer’s mouth:

We need to develop some key messages we can use to market to our target audience.

Yikes. So much not to like in there. Let me break this one down.

Audience

You hear companies talk about their “target audiences” all the time. So what’s wrong with that?

The word audience implies that the company is talking and the people on the other end are listening. This sort of binary, transactional description of the relationship seems so dated to me.

Certainly in the glory days of advertising where companies had the podium of TV, magazine, and newspaper ads, the word audience was more appropriate. After all, no one ever got far talking back to the TV set.

But in the age of Twitter and Facebook, companies must respect that everyone has the podium. Everyone is talking, everyone is listening.

Where most marketing folks would use the word audience, I often substitute the word community. By thinking of those who surround your brand as members of communities rather than simply as ears listening to you, you’ll already be on your way to a healthier, deeper relationship with the people who engage with your company.

Message

The word message bothers me for the same reason. It is such an antiquated, transactional term. When a company talks about “creating messaging” or “delivering targeted messages” I start thinking we should call the Pony Express.

I believe the move to a community-based approach begins when you quit worrying about “delivering messages” and begin thinking about sharing stories, joining conversations, or sparking dialogue.

These are much better ways to communicate authentically in a collaborative world.

Market

Perhaps the word that bugs me most is market (used as a noun or a verb) and its related friend consumer. Companies that think of people interested in them as consumers or markets take what could become a multi-dimensional relationship and whittle it down to one dimension: a transaction.

If you think of someone as part of your “target market” or a “consumer” you are making your interest in them abundantly clear. You want them to consume something. You want their money.

But what if there were more that people who are interested in your brand could share besides just their money? Perhaps they have valuable ideas that might make your company better? Perhaps they’d be willing to volunteer to help you achieve your mission in other ways?

When you stop thinking of the people that care about your company as consumers or a market, you can begin to see opportunities that you would have been blind to before.

Want an example? Look anywhere in the open source world. Sure there are buyers and sellers, but there are also lots of people bringing value in other ways. Developing code. Hosting projects. Writing documentation. The list goes on.

So let me be the first to admit these three words are the tip of the iceberg. Moving a company from a marketing-based to a community-based approach to building relationships will take more than changing a few words. It will require you to embrace new media, new skill sets, and a totally new way of thinking.

But you have to start somewhere.

Do you see other things that may need to change as we move from a marketing-based to community-based approach to building brands and companies?

I’d love to hear your ideas.

[This post originally appeared on opensource.com]

Mitsubishi’s gift to the community of people affected by the Japan earthquake

When corporations engage with communities, many make the mistake of focusing first on what the community can do for them. I encourage companies not to start with the benefit they get from the community (buy my stuff! design my products! give me feedback!), but instead with the benefits they give to the community.

When corporations engage with communities, many make the mistake of focusing first on what the community can do for them. I encourage companies not to start with the benefit they get from the community (buy my stuff! design my products! give me feedback!), but instead with the benefits they give to the community.

What can corporations bring to the table that helps communities? Some examples:

• Funding: Companies can invest real money in projects that help the community achieve its goals.

• Gifts: Many communities are in need of assets that individuals can’t buy on their own. Are there assets the company already owns or could buy then give to the community as a gift?

• Time: The company probably has knowledgeable people who might have a lot to offer and could spend on-the-clock time helping on projects that further community goals.

• Connections: Who do people in the organization know and how might these relationships be of value to others in the community?

• Brand power: Could the company use the power of its brand to shine the light on important community efforts, drawing more attention and help to the cause?

This weekend, a story in The New York Times highlighted one example of a company that brought great value to a community in need with a well-timed gift.

After the March earthquake in Japan, many affected areas had electricity restored relatively quickly. Gasoline, however, still proved hard to come by.

So Mitsubishi president Osamu Masuko donated almost 100 of his company’s i-MiEV electric cars to help ensure people and supplies could keep moving in the affected areas.

This gift, which cost Mitsubishi relatively little, has provided a huge benefit for the affected communities. One story from the article:

“There was almost no gas at the time, so I was extremely thankful when I heard about the offer,” said Tetsuo Ishii, a division chief in the environmental department in Sendai, which also got four Nissan Leaf electric cars. “If we hadn’t received the cars, it would have been very difficult to do what we needed to.”

Mr. Ishii and other officials in Sendai assigned the cars strategically. Two were used to bring food and supplies to the 23 remaining refugee centers in the city, while two others served doctors. Education officials have been using another two vehicles to inspect schools for structural damage. Others helped deliver supplies to kindergartens around the city or were loaned to volunteer groups.

Most corporations would view a gift like this as simple corporate philanthropy. But I believe giving back to communities is much more than a “do good” strategy. I believe it can be good business as well.

Mitsubishi’s story is a case in point. Not only has Mitsubishi garnered goodwill from citizens appreciative of the gift, they have created a wonderful, emotionally-resonant proof point of the practicality and reliability of electric vehicles at a time when many are still questioning how effective they will actually be.

The people at Mitsubishi will not only be able to sleep at night knowing they provided a valuable gift to a community in need, but they will also have a powerful story that can be used for years down the road illustrating the effectiveness and practicality of the electric vehicle.

The community benefits. The company creates value for its shareholders at the same time. In my view, gifts like this where everyone wins are the best gifts of all.

[This article originally appeared on opensource.com]

The astrophysics of building a brand from the inside out

It has been a while since I wrote an original post on this blog, so I thought over the next few months I’d try to make up for lost time by previewing some of the concepts from my new book The Ad-Free Brand: Secrets to Successful Brand Positioning in a Digital World, due out in August. If you like what you see, let me know. If not, well, I still have some time to make edits, so let me know that as well. But be gentle.

It has been a while since I wrote an original post on this blog, so I thought over the next few months I’d try to make up for lost time by previewing some of the concepts from my new book The Ad-Free Brand: Secrets to Successful Brand Positioning in a Digital World, due out in August. If you like what you see, let me know. If not, well, I still have some time to make edits, so let me know that as well. But be gentle.

One of the key concepts in the book is that ad-free brands are brands built from the inside out. But what exactly does this mean?

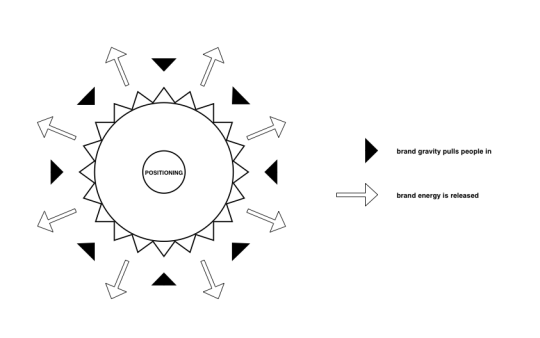

Imagine for a second that a brand is a powerful star at the center of a solar system, maybe one like our Sun. For me, brand positioning is an attempt to describe the gravitational pull at the very center of that star.

Great brand positioning creates gravity that pulls people closer to the heart of the brand. As people move closer, the brand releases energy, in much the same way a star sends out heat and light.

So when beginning to roll out new brand positioning, one way to think of your work is as an attempt to mimic thermonuclear fusion within a star. No small feat, huh?

We want to pull people closer to the center of the brand using the brand positioning as a gravitational force. Then, just like with atoms in a star, once the core group of people at the center of the brand is sufficiently dense, a reaction occurs, resulting in a continuous stream of brand energy released over time. The denser you can make the core near the center of the brand, the more energy is released.

If you aren’t the least bit interested in astrophysics, or that explanation above did not resonate with you, let me try another, simpler one:

If you aren’t the least bit interested in astrophysics, or that explanation above did not resonate with you, let me try another, simpler one:

At some point, if enough people begin to deeply understand and live the brand in their daily work, magic happens.

American showman and circus entrepreneur P.T. Barnum was no astrophysicist, but he understood the power of this magic moment. His explanation: “Nothing draws a crowd like a crowd.”

Aligning a core, closely aligned group of people around the brand positioning is the only way to set off this particular reaction. And there is no better place to start rolling out your positioning than with those people who already work for your organization and have a vested interest in its success.

Building a brand from the inside out means building the brand by creating energy with the community of the people closest to the brand—those who work for the organization—and using the gravitation force this group creates to pull even more people close to the center of the brand.

How do you sell a community-based brand strategy to your executive team?

One of my favorite regular blog subjects is how to use community-based strategies to build brands. In fact, I’m putting the finishing touches on a new book entitled The Ad-Free Brand: Secrets to Successful Brand Positioning in a Digital World which will be out this August and covers exactly that topic.

One of my favorite regular blog subjects is how to use community-based strategies to build brands. In fact, I’m putting the finishing touches on a new book entitled The Ad-Free Brand: Secrets to Successful Brand Positioning in a Digital World which will be out this August and covers exactly that topic.

How does a community-based brand strategy work? Simple.

Rather than staying behind the curtain and developing a brand strategy inside your organization for your brand community, you step out from behind the curtain and develop the strategy with your brand community.

Many traditional executives will have a hard time with this approach. First, it means the organization will need to publicly admit it does not have all the answers already. Some folks (especially executives, in my experience) just have a hard time admitting they don’t know everything.

Second, it means ceding some control over the direction of your brand to people in the communities that care about it. The truth is that you probably already have lost absolute control of your brand because of the impact of Twitter, Facebook, blogs, and other user-controlled media. Some folks just aren’t ready to accept that fact yet.

If you are considering opening up your brand strategy to help from people outside the organization, how do you sell the approach to hesitant executives? Why is this new model not just good philosophy, but also good business?

Here are the five key benefits of a community-based brand strategy:

Does your organization think like Ptolemy?

Who is in your community? It seems like such a simple question.

Who is in your community? It seems like such a simple question.

In reality, your organization probably doesn’t just interact with one community, but a whole host of very different communities and sub-communities. The only thing these communities may share is that they are made up of individual human beings.

When asked to list the groups of people making up an organization’s community, most would probably end up with a list that looked something like this:

B Corps: new advancements in a community advancing our communities

B Lab, the organization behind the growing community of B Corporations (companies using the power of business to solve social and environmental problems) or B Corps for short, recently released its 2011 annual report.

B Lab, the organization behind the growing community of B Corporations (companies using the power of business to solve social and environmental problems) or B Corps for short, recently released its 2011 annual report.

The report highlights some interesting progress over the last year, including a 75% increase in the number of certified B Corps, with larger businesses also joining the growing movement.

But the theme within the report I found particularly compelling is that the community of B Corps is now becoming large enough to exert a gravitational force of its own with the power to impact public policy while also creating opportunities for member corporations to help each other.

A few examples:

In 2010, with the encouragement of B Lab and the community of B Corps, legislation passed in both Maryland and Vermont creating a new type of “benefit corporation” with a legal responsibility to work for the good of the communities they serve, not just for the profit of their shareholders. Nine additional states in the US are set to move forward with similar legislation in 2011.